Beow Tan harassing minorities, the racial slur and kicking incident in Choa Chu Kang, the former Ngee Ann Polytechnic lecturer’s racist confrontation and as recently as last week, the racist remarks and assault at East Coast Park.

These are just a few events that reflect an increased resentment between the races. It’s also a stark reminder to Singaporeans that racial tensions and disharmony aren’t yet obsolete even in the most cosmopolitan of nations.

It was in recognition of the perils of racial disharmony that the Ethnic Integration Policy (EIP) was introduced back in 1989. More commonly referred to as the HDB ethnic quota, the EIP was meant to discourage the forming of racial enclaves in Singapore.

It is human nature to seek the company of your own group, be it along racial lines or otherwise. Our government recognised that the risk of our three main ethnic groups in Singapore — Malays, Chinese and Indians — segregating themselves over time is real. Hence the implementation of the ethnic quota under the EIP.

What is the Ethnic Integration Policy (EIP)?

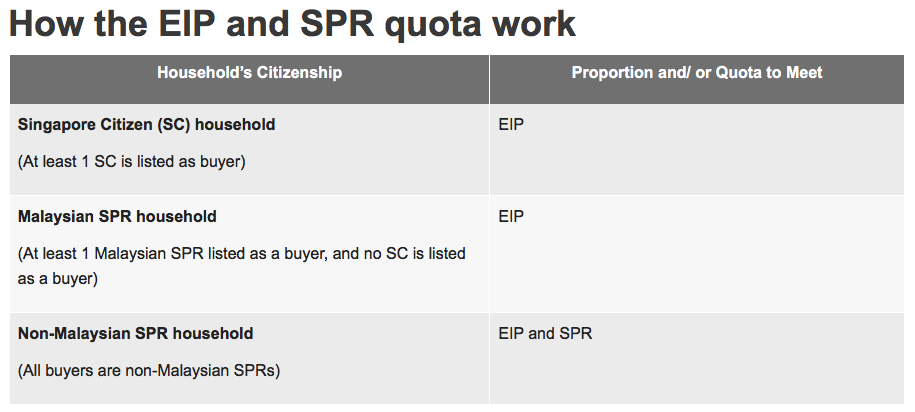

The EIP is just one of the many initiatives that have been put forward by the government in the hopes of fostering better integration and respect between the various ethnicities in Singapore. The policy is similar to the Singapore Permanent Resident (SPR) quota implemented by HDB.

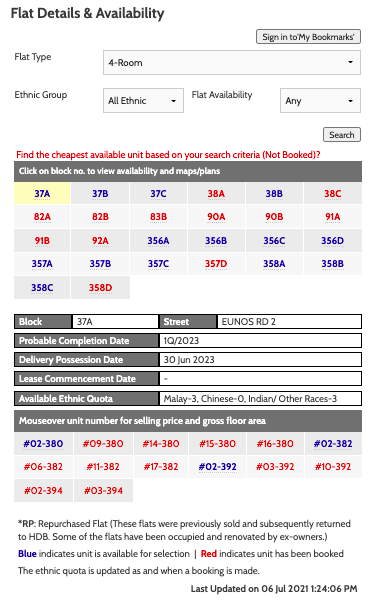

Under the EIP, limits are set on the total percentage of a block or neighbourhood that may be occupied by a certain ethnicity. These limits, which are updated on the first of every month, are meant to reflect the racial composition in Singapore.

What this means is that while people are free to buy and sell their flats if they’re of the same ethnicity (since this won’t affect the percentage of ownership), should they want to buy or sell from someone of a different ethnicity, they will only be able to do so if the sale won’t result in the percentage of that ethnicity going over their allotted quota.

(EIP quotas based on ethnic proportions are updated on the first of every month. Check if you fulfil the EIP quota of a specific block/neighbourhood via HDB’s portal.)

The impetus for such a policy was the government’s recognition of a growing trend of Singaporeans to form certain ethnic enclaves. Bedok, for example, was inhabited predominantly by Malays, while the Chinese favoured settling in Hougang. There’s also the fear that such a division would beckon the return to the 1960s level of distrust amongst the different races in Singapore, which led to some of the most devastating riots in our short history as an independent nation<.

Effects and criticisms of the Ethnic Integration Policy

To the government’s credit, the EIP has been successful in its main aim of preventing the ‘racial enclaves’ it was engineered to avert. Each HDB estate is a melting pot of races, with a certain degree of interaction and integration amongst the different races.

But its successes have come with a string of criticisms as well, particularly in respect of how the EIP tends to disadvantage certain ethnicities over others, as recently debated in the parliamentary session yesterday.

1. The EIP leads to some BTO units being left unpicked in land-scarce Singapore

As reported in Census 2020, there’s a difference in the household income between the three major races of Singapore.

The effect of this is visible in HDB’s build-to-order (BTO) flat selection processes, where there are unfilled Chinese quota leftover flats in cheaper, non-mature estates such as Tengah and unfilled Malay quota leftover flats in more expensive, mature estates such as Geylang.

For instance, despite the high application rate, a total of 42 four-room units from the Dakota Breeze and Pine Vista BTO (launched in the May 2017 sales exercise) were put up for sale during the November 2020 SBF. As of writing, three units are still available for selection. But they’re only available for Malays. No Chinese can buy these vacant units under the EIP.

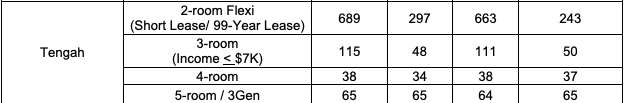

On the other hand, we see a reverse of this in Tengah, the newest non-mature estate in Singapore. During the last SBF exercise in May 2021, a higher number of 2-room Flexi and 3-room units were available for Chinese applicants. These units are all leftovers from previous BTO launches in the estate, since as of writing, none of the projects has been completed yet.

Given the above, critics may argue that given Singapore’s land scarcity, it is perhaps a bit foolish to rather leave these units unpicked than allocating them to citizens with a genuine housing need.

2. It may lead to price differences in the same property

According to a 2012 study, Chinese-constrained HDB resale units (i.e. only Chinese buyers eligible) were 5 to 8% more expensive than Malay or Indian-constrained units, which were 3 to 4% cheaper than the average resale price. This could mean that flats owned by the Chinese were more likely to sell at a price over HDB valuation, whereas flats owned by Malay or Indians were more likely to sell at below HDB valuation.

Besides the rather unfair situation of two — almost identical — flats being sold for a huge difference in price simply because of the ethnicity of the person to whom the flat could be sold, this fact also highlights the possibility that the ethnic quota could be making racial income inequality worse.

As a recent opinion piece argues, the system “financially benefits one family over another purely on the basis of race”.

3. The policy could make it harder for people to sell their flats

One of the major gripes with the racial quota is that it often results in sellers, who are ready and willing to sell their units, having to turn away willing buyers, simply because the buyer is of the ethnicity whereby the quota has been maxed out.

In today’s HDB resale market, these restrictions are doubly punishing. It has resulted in many sellers being unable to sell their flats, even when they’ve had offers, just because of ethnicity.

4. It might miss certain marks with our increasingly mixed heritage

In Singapore, children of mixed-race marriages are entitled to register a double-barrelled race. A daughter of Malay and Chinese parents, for example, can therefore register as a Malay-Chinese or Chinese-Malay.

Under the current EIP policy, only the first race component of the double-barrel may be used. Therefore, if our hypothetical daughter above had registered as a Chinese-Malay, she would be restricted by the quota restrictions imposed on Chinese occupants, regardless of the fact that she technically is also half Malay.

With the numbers of mixed-race marriages on the rise — about one in five of all marriages in 2019 were mixed-race couples — the EIP policy could potentially miss the mark in its consideration of such mixed-race families.

5. It assumes living together means integration

The Ethnic Integration Policy works on the assumption that by living in close quarters, residents of different ethnicities will be forced to mingle and interact with each other, thereby strengthening the racial harmony and unity in Singapore.

However, this begs the question: does living together equal, or necessarily lead to, integration and understanding?

Singaporeans, by and large, tend not to mix around or even acknowledge their neighbours, which means the core function of the EIP may not always be the only tool that works.

Just look at the recent gong incident, in which a Chinese woman started hitting a gong while her Indian neighbour was carrying out a prayer ritual.

And then there’s the case of Amy Cheong back in 2012, who took to social media to complain about her Malay neighbours who were holding a wedding at the void deck and went on to disparage the Malay society as a whole.

Certainly, these cases have shown that proximity does not necessarily breed understanding.

It’s therefore been argued that what needs to be championed instead are “common spaces” or “bridging social capital” between communities. This means having events and encouraging community participation between people of different races, rather than maintaining a strict focus on housing quotas. This would arguably be harder work, but perhaps, a better solution.

Should the Ethnic Integration Policy be removed?

The EIP, and its prescriptive and rigid natures, is undoubtedly one of the most talked-about policies in Singapore. Each person here will have their own view on whether it should remain, be tweaked, or abolished in its entirety.

There are definitely some strong arguments against it. From the disadvantages it imposes on sellers, to questions on its efficacy in bringing the community together. And let’s face it, it feels like your parents forcing you to eat your vegetables with the true but tired line: it’s good for you, so do it!

Nonetheless, it would be hasty to do away with the EIP completely. The US, UK and France are prime examples of countries that, in allowing pure market forces to drive homeownership, have led racial enclaves to form. And it would be foolish to think that we won’t slowly revert to such a situation ourselves in the near future.

Perhaps what’s required instead is a fine-tuning of the system, as brought up in the recent parliamentary session. On top of the appeals, a little more flexibility into the strict, absolute controls on percentages also takes into consideration market difficulties when enforcing such controls.

[Read more about our suggested tweaks on the policy here.]

At the same time, more work needs to be done to put in place actual initiatives to encourage the mixing of the races in Singapore, rather than hoping that mere proximity will do all the hard work.

As the recent racist incidents have shown, we’re just not there yet when it comes to racial sensitivity and acceptance.

What do you think of the Ethnic Integration Policy? Let us know in the comments section below.

If you found this article helpful, 99.co recommends Your Question Answered: Can a Singapore PR buy an HDB flat? and We need to talk about racial discrimination in Singapore’s rental market.

Looking for a property to buy or rent? Find your dream home on Singapore’s largest property portal 99.co! If you have an interesting property-related story to share with us, drop us a message here – we’ll review it and get back to you.

The post Is the HDB Ethnic Integration Policy and ethnic quota still relevant? appeared first on 99.co.