Recently, some friends and I were discussing how the costs of car- and house-ownership in Singapore are controlled through different policies and restrictions.

While the cost of car ownership is often tied to how high the Certificate of Entitlement (COE) premium is, a bulk of the cost in home-ownership depends on the buyer and seller, home valuation and for folks with more than one property, the Additional Buyers’ Stamp Duty (ABSD).

COEs are quota licenses required to own and drive a vehicle in Singapore. They are usually good for 10 years and are included in the price of vehicles.

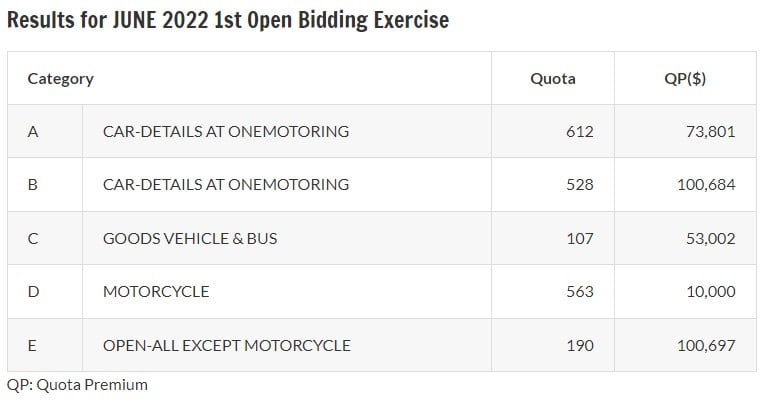

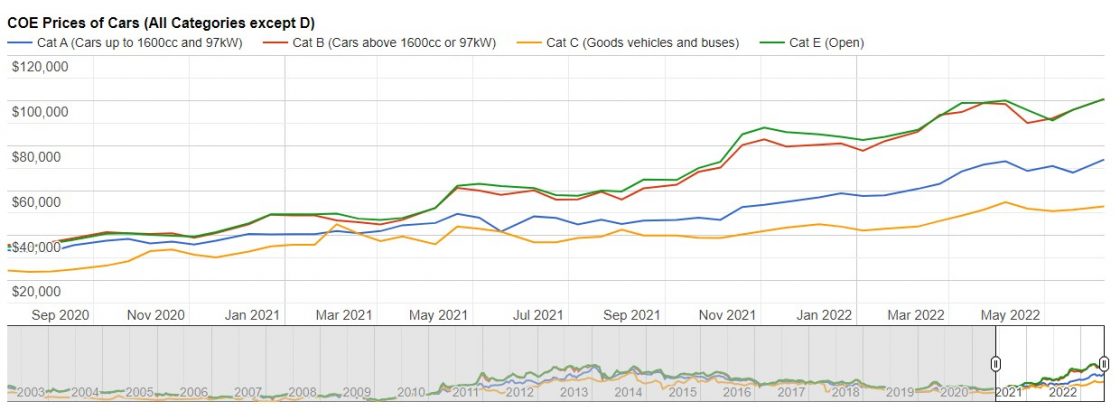

Just a few days ago, the COE premium for Category B cars (engines >1,600cc or 130bhp, or EVs with power output >110kW) and the Open category (often used for larger cars) – breached the S$100,000 mark. They’re the highest premiums ever seen since 1994.

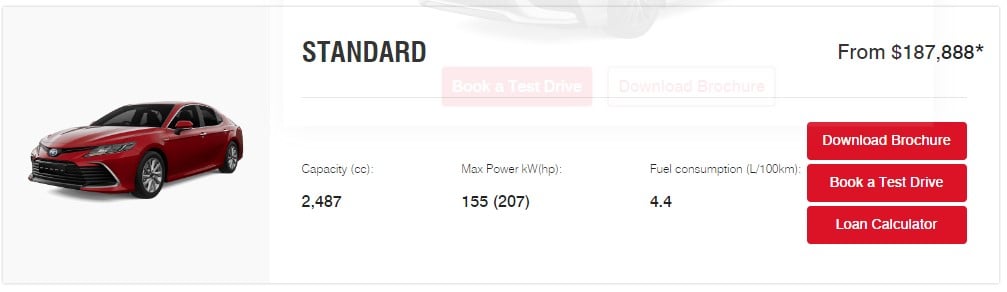

So a standard 5-seater, 2,487-cc Toyota Camry (Category B vehicle) today would roughly cost about S$188k. That’s nearly half the price of a 4- or 5-room HDB BTO flat in Jurong or Yishun (before grants).

Notably, premiums in other vehicle categories also rose in the latest exercise. For example, Category A cars (with engines up to 1,600cc and 130bhp, or EVs with power output up to 110kW) went up from S$68,001 to S$73,801.

According to many car dealers, they do not expect these recent sky-high premiums to come down until at least 2023 (when 2013-registered vehicles are scrapped and more COEs are recirculated back into the system).

Several experts cited the following reasons for the increase:

- There is a tighter supply of COEs issued by the government.

- There is a tighter supply of new vehicles entering the market as authorities maintain a zero growth rate per annum policy for cars and motorcycles until January 2025.

- There is greater demand for vehicles – especially in the larger car categories – as families need to transport their elderly and children more frequently.

- There are more high-net-worth individuals and families living and moving to Singapore (eg. expatriates, family offices, etc.) who want to own a vehicle no matter the cost.

While COE isn’t the only tool used by the government to control private vehicle growth in land-scarce Singapore (vehicle tax, supply, etc. are a few others), it is often seen as a deterrent to “buy a car” or if you’re already a car owner, to “buy more cars”.

Based on this model, one of my friends then asked why not consider utilising the COE system to also control home ownership? This way, as the “license to own a home” is limited, it could serve as a deterrent for existing homeowners to “buy more than one house” while giving non-home-owners a greater entry point to own one.

The discussion turned into a for and against session, with neither side reaching a conclusion. I’ll summarise some of the points of our debate here:

For: How a COE model would benefit Singapore home ownership

The current COE model separates vehicle quota and premiums into five distinct categories: Category A (cars up to 1600cc), Category B (cars above 1600cc), Category C (commercial), Category D (motorcycle) and Category E (open). The available quotas and submitted bids from dealers for different categories determine the eventual COE premium for each vehicle category every month.

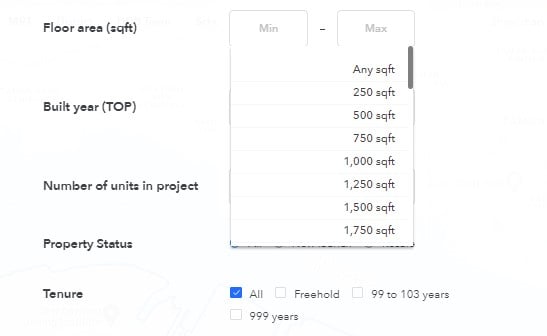

Similarly, what if there is a “COE-equivalent” for residential home purchases based on liveable square-foot space. For example, a Category A for homes with up to 749 square feet of living space, a Category B for homes between 750 and 999 sqft, a Cat C for 1,000 to 1,249 square feet, and so on.

From the outset, every existing homeowner or co-owner is given a corresponding license in their respective category. For example, if a homeowner has two apartments, one that’s 600 sqft and another that’s 1,000 sqft, he would have a license for Category A and Category C. These licenses are tied to the tenure of the apartment.

When he sells his apartment, the new owner has to pay for the license and its ownership is transferred to the latter. If the new owner has recently sold his own apartment, which is the same size category as the new apartment, then the costs of the licenses should effectively cancel each other out. Any cost differences (due to different time of sale, or space categories) are paid out to the government.

Every month, based on the number of existing category licenses in the market, how many were exchanged in the resale market and how many new homes are set to launch, the authorities can predetermine the quota for new licenses to be issued.

As demand for more 5-room and executive flats increases (whether it’s BTO, HDB resale or condo), the cost of licenses for larger spaces will rise. These premiums are added on to the cost of these flats but can be subsidised for first-time applicants (eg. first HDB unit – BTO or resale) or discounted if it’s their only home. Think of it as a “reverse ABSD” to encourage more first-time homeowners.

Furthermore, the successful issuance of licenses can be prioritised based on nationality on a monthly basis. For example, larger space category licenses for Singaporeans, then PRs and foreigners, and vice versa.

Ultimately, the idea behind a licensing system for liveable space regardless of property profile (private or public, how many bedrooms, etc.) is to ensure sufficient liveable space opportunities for Singaporeans, PRs and foreigners.

In other words, folks who buy more than one home or larger spaces will have to pay more. Someone who capitalises on selling his 3-room HDB BTO flat for a larger 5-room condo will pay more for the upgrade – not only in psf and total pricing but the cost of upgrading to a different space category. Alternatively, he can settle for a same-category-sized condo (so the costs of the licenses cancel each other out).

Eventually, with market forces and quotas guiding these licensing costs, there may not even be a need for additional taxes or ABSD, as these costs may more than replace the lost revenue.

For home buyers and upgraders, the potential rise and ebb of monthly licensing costs could make for a more robust market to buy and sell their properties. Not only that, a savvy homeowner holding on to his home ‘COE’ may potentially reap additional benefits in the future as demand for his liveable space category outstrips supply.

While the property sector saw its stamp duty revenue hitting S$6.84b in 2021, vehicle taxes and COE revenue is set to reach S$6.46b in 2022. In fact, during Budget FY2017, car taxes and COE premiums were projected to be around S$9.2b in revenues. From a revenue perspective, there is potential for both models to work, or in some hybrid form at least.

Against: Why a COE model would not work for home ownership

While we agree that COE serves as a cost-deterrent in buying a car, or buying more than one car, applying it to homeownership will only backfire as they do not fall under the same asset class.

First, most view homes as an appreciable asset class. Not everyone sees their cars the same way. In fact, the car would have lost some value the moment you collect your key and ignite the engine. It’s not the same as an apartment in Singapore.

Second, the cost of home ownership based on liveable space is already factored in the per-square-foot pricing premium of the property type and size. This cost already covers the location, floor level, view, amenities, neighbourhood and developer costs. Adding an additional licensing cost based on square-foot categorisation would not only make the property pricier but deter potential home buyers who wish to upgrade.

Third, there aren’t as many larger-spaced apartments (lofts, maisonettes, executive apartments, penthouses, etc.) in the market as there are small- to mid-sized apartments. Restricting the issuance of licenses based on residential status for these unit types would severely lower their demand, say penthouses, landed houses (eg. GCBs) and larger-sized apartments of new launch properties among Singaporeans, PRs and foreigners.

It could potentially impact the sell-through of these properties and severely affect developers’ bottom lines.

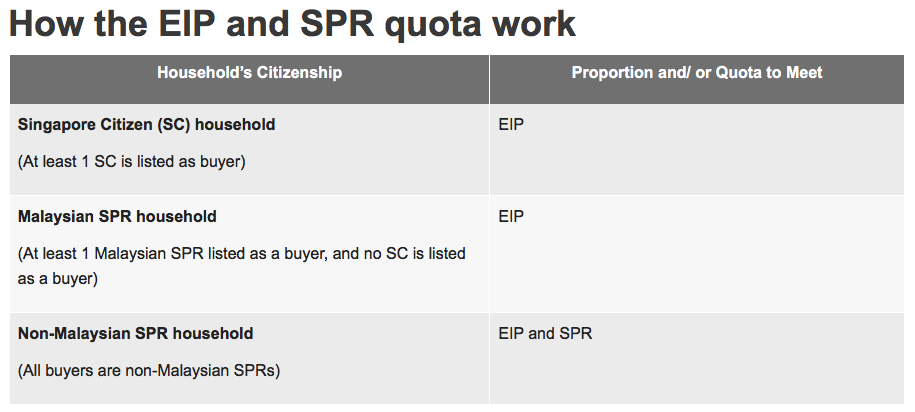

Fourth, the current ABSD model has a tiered structure when it comes to multiple property ownership. For PRs, it is already increasingly expensive to own a 2nd property. For foreigners, buying their first is already taxable from the get-go. It does not make sense to attach a new or different cost structure where anybody can buy multiple homes as long as they have the license and money.

| Types of buyers | Rates on or after 16 December 2021 | |

| Singapore Citizens | First residential property | 0% |

| Second residential property | 17% | |

| Third and subsequent residential property | 25% | |

| Permanent Residents | First residential property | 5% |

| Second residential property | 25% | |

| Third and subsequent residential property | 30% | |

| Foreigners | Any residential property | 30% |

| Entities | Any residential property | 35% (Plus additional 5% for housing developers (non-remittable)) |

Fifth, the quota and bid structure from the COE model can be dangerous if applied to the housing model. This is because the lifecycle of property supply and demand is not the same as the lifecycle of new/old vehicle supply and demand.

There are bound to be loopholes which may be exploited by savvy property investors and upgraders. This, in turn, causes runaway home prices, making them out of reach for genuine buyers. This would effectively render the model a failure.

Finally, the COE model is a necessity to control the vehicle population due to land scarcity and the road system we have here in Singapore. Together with the Vehicle Quota System (VQS), the system is overseen by the Land Transport Authority (LTA).

Introducing a similar model in the property sector would mean involving agencies like the Ministry of National Development and Urban Redevelopment Authority (URA). Such an undertaking would be stressful and a failure to balance expectations could spell disaster in maintaining overall equilibrium for home development, ownership and pricing.

–

So are you for or against – or perhaps a hybrid model? Let us know in the comments section below or on our Facebook post.

If you found this article helpful, 99.co recommends What you need to know about the new ABSD (Trust): 35% rate + conditions for remission and Full list of new launch condos (with unsold units) approaching their developer ABSD deadlines in 2022/2023.

The post Would a COE model work in our housing plans? appeared first on 99.co.